25.11.20

Alma De Groen is the incredible playwright behind Wicked Sisters, as well as one of Australia’s greatest playwrights. Her career has spanned decades, and she was Griffin’s first ever Literary Manager. To celebrate the revival of her play, Alma was kind enough to take the time to reflect on her career, enlightening us with wonderful tidbits of Australian theatrical history. Read on!

The revival of Wicked Sisters, after almost twenty years, prompted me to think back on how my life in theatre began, so I put down a few memories as they came up. Not a think piece, more a sort of gratitude memoir:

Chance—or mischance—in the 1950s brought an Oxford graduate to teach fifth form English at a remote hydro town in New Zealand. A place so provisional and basic that half the little pre-fab houses were towed away when the dam was finished. I never knew why he was there in his tweed jacket with leather patches on the elbows or for his love of Katherine Mansfield and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Oxford may have been an invention. In any event, one memorable night, he took us on a long bus ride to Rotorua to see the New Zealand Players perform Shaw‘s Saint Joan, with Edith Campion, later mother of Jane Campion, as Saint Joan.

Without him I might have been someone who never got to see live theatre at all. Ever.

Belinda Giblin as Lydia in ‘Wicked Sisters’, Griffin Theatre Company (2002)

In 1964, an unexplained chance prompted a workmate I hardly knew to ask me to be her bridesmaid. I claimed to be going overseas and quickly bought a ticket to the furthest place I could afford—Australia. The runaway bridesmaid.

In Sydney, I saw my first Australian play, A Refined Look at Existence by Rodney Milgate. I remember some knitting that extended across the stage, and sound effects of a toilet flushing offstage. I thought: “I could do that”. I hung about outside until the actors came out but was too much in awe to speak to them. I’m still in awe of actors.

My next visit drove that up to the heights: Brian Syron‘s in-the-round production of the prison play Fortune and Men’s Eyes at the Ensemble. Across from me I could watch audience members’ jaws dropping. Brian, who knew something about prison, had built a giant cage, and we were looking through the bars at the terrifying presences of inmates Max Phipps, Max Cullen and Sandy Harbutt, so brutal and scary I would never have dreamed of waiting outside to meet them!

But I did meet them, and Sandy stood over Brian Syron until he read my first play. Brian, beautiful and charismatic and inspired by the works of Tennessee Williams, had worked as a model to get to New York and inform the famous acting coach Stella Adler that she had to take him on. She did, eventually making him her teaching assistant.

Brian looked at me and said, “You are a playwright”.

Then I met a representative of the Sydney theatre establishment, Robin Lovejoy, head of The Old Tote Theatre Company. He looked at me from behind his desk and said:

“You don’t belong in the theatre. You are a housewife”.

Sitting there in my cotton frock, I suppose I was. I’d been described that way in Canada, where a newspaper heading about my play The Joss Adams Show had said: “Housewife wins Prize in Nationwide Playwriting Competition”.

Poster for ‘The Joss Adams Show’ at the Pram Factory (1972)

We were upstarts, the women writers who attempted to break into theatre. When Jane Street in 1973 presented my play, The After-life of Arthur Cravan, about the notorious belle époque poet and boxer, followed by Dorothy Hewett‘s Bon Bons and Roses for Dolly, I had no idea what an intrusion we were. Dorothy’s play made a reference to menstrual bleeding that caused alarm and dismay, and H.G. Kippax, the chief reviewer in town, described the play as having “all the sense of construction of an egg beater”. Cravan became an early lesson in the kind of reviews I could expect: “If you happen to find yourself driving past this theatre, keep going. Don’t, whatever you do, go inside.”

I wrote nothing for six months.

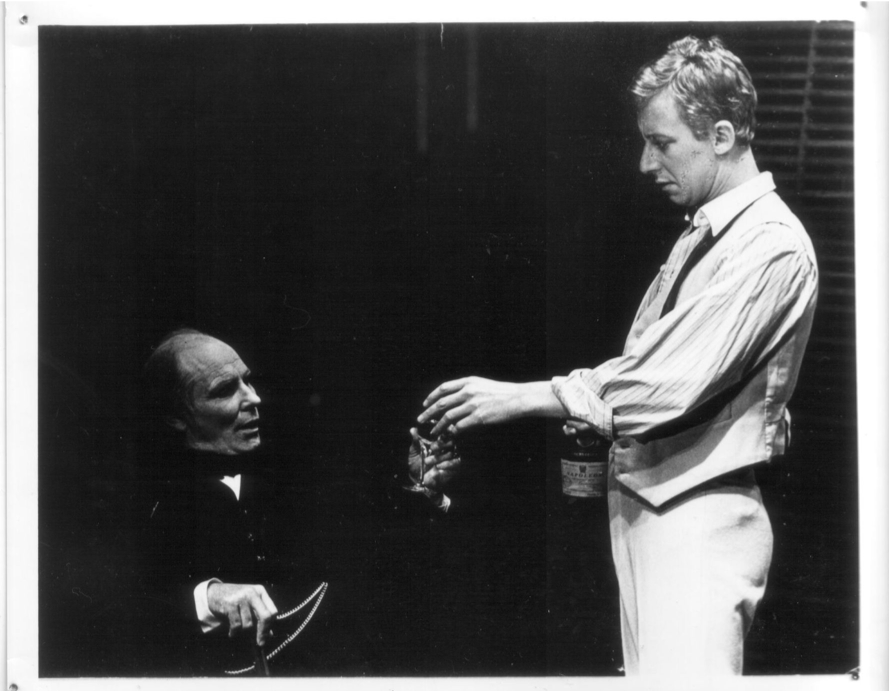

John Faassen as Oscar Wilde and Max Phipps as Arthur Cravan in ‘The After-life of Arthur Cravan” at Jane St Theatre (1973)

But Max Phipps had become my Cravan, and Sandy Harbutt—later writer, director and star of the cult bikie movie Stone—took me to my opening night on the back of his Kwaka 900. Sandy had married Helen Morse, the actress I came to wish for in every play I wrote, and I moved into the flat next to “Phippsy”—who was still sometimes scary, but in a diaphanous black negligée on Sundays, less so.

Brian Syron, in the early seventies, started The Australian National Playwrights’ Conference (ANPC). I had few connections with established companies (“You don’t belong in the theatre”) so I relied on the Conference to workshop five of my plays over the years. At ANPC, the work was presented in front of an audience of professionals and I was in with a chance of a production. At first we were an odd mix of amateur aspirants, running back and forth from our workshops to our typewriters in the pre-fabs set up for us. One of the hopeful playwrights asked if I visualised what was happening on stage while I was writing. As time went on it became more professional, and guests from overseas were invited: Howard Brenton, Trevor Griffiths. Margaret Whitlam became our patron, bringing her knitting to workshops. Betty Roland, writer of The Touch of Silk, produced to acclaim in 1928, was an honoured guest, and Mona Brand was there in 1983. I’m ashamed to say—such was the obscurity into which women of accomplishment could be flung—many of us had zero knowledge of the career of this left-wing activist who had had more plays produced worldwide than many well-known playwrights in Australia, which had never, according to Wikipedia, produced any of hers professionally.

There were other women playwrights of an earlier era who never got to see their work professionally performed. Dymphna Cusack (co-author of the novel Come in Spinner) wrote a powerful play, Morning Sacrifice, set in the staff room of a girls’ high school on the eve of the Second World War. Written in 1942, it was given its first professional production by Griffin in 1986. Being privileged to see it showed me how starved we were of female experience on stage, depicted truthfully, with an awareness of the suffocating reality of these women’s lives. Patronising reviews of the play, which deemed it dated, ignored the relevance it had for women.

In the Ladies at interval:

“Nothing much has changed. I stay out of the staff room as much as possible.”

“Twelve days relief teaching—that was enough for me!”

Women can write differently from men. These days, when “strident” and “shrill” are no longer the first words reviewers reach for, we get to see this on stage. Mary Daly, author of Gyn/Ecology, freed me with the words: “Women should not take this reality too seriously, since it may not be the only one”.

Bringing focused feminism to playwriting meant the strangeness of The Rivers of China, a play that really only made its purpose clear when staged, met with incomprehension, sometimes embarrassed incomprehension, from every theatre professional who read it. It would have been sunk without the Playwrights’ Conference. Anne Harvey was director in 1986, possibly the first woman, I’m not sure. Anne said, “I don’t understand it, but I trust you and we’ll take it”. The reading included Helen Morse, John Howard and Robin Ramsay at 9 o’clock on a Sunday morning. It was spare, hypnotic and clear, my favourite memory of any of my plays. It was unusual to see men in tears, including the powerful John Howard. John Sumner at Melbourne Theatre Company wrote to say he had read it “with some bewilderment” but planned to do it. And Richard Wherrett at Sydney Theatre Company took it as well. Such was the effect of the ANPC in those days.

‘Wicked Sisters’ in Poland (2018)

With Wicked Sisters at Griffin I’ve come full circle. The denizens of the Stables in the early 1970s put on my first play, The Sweatproof Boy, with Richard Wherrett directing. That it happened at all was because of word of mouth via Brian Syron and Katherine Brisbane in the days before Currency Press existed. I owe them. Brian liked to say it to me quite often: “You owe me”. And it’s true. Chance and luck and gratitude.

My thanks and gratitude to all at Griffin too, and to Lee Lewis, for this revival.

Alma De Groen

November 2020

Wicked Sisters plays at the Seymour Centre until 12 December.