18.04.19

Adriano Cappelletta is the writer, and one of the performers, of Never Let Me Go, playing for four nights as part of Batch Festival 2019. For this In Conversation piece, Adriano details the rich history of AIDS in Australia, which serves as the inspiration behind the piece.

I am a gay man who became a teenager in the early ’90s, where there was scant representation of gay people in media, stories and films that wasn’t steeped in stereotypes like the limp-wristed designer, or the fabulous best friend (Martin Short in Father of the Bride anyone? “Welcome to the 90s, Mr. Banks!”).

There were, however, stories that began to emerge about a mysterious disease called AIDS. I remember watching the Grim Reaper commercial as a kid and being aware of something ominous, but being unsure if it was ten pin bowling I should be afraid of (though that message certainly accorded with my aversion to sports!).

As I grappled with the secret of my sexuality, I realised I wasn’t going to change—this is who I was. The dots began connecting and it became clear that men like me were dying. I vividly remember sitting in the cinema on my 15th birthday watching The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and being stunned when the bus was graffitied with “AIDS FUCKERS GO HOME” during one unsuccessful stay in a country town. Struggling with my sexuality as a teenager, I didn’t have a sexual awakening or tender first love, but rather the fear of death and intimacy and sex. It was bad enough grappling with rampant homophobia and the fear that family and friends could reject me, but add to that the knowledge that if I acted on my feelings I could contract a fatal disease. It was sobering to say the least.

I was scared to come out to my parents, not only because I didn’t know how they would react, but because they could be worried that I may die. It just added to the tragic gay scenario.

The hysteria around AIDS, the uncertainty, the tragedy of lost lives, and the moralising that this disease was some sort of punishment, weighed on me as a young man. I wasn’t excited to start my fabulous gay life.

I moved from Perth to Sydney when I was 21, and was introduced to a world of dance parties, gay bars and being part of an accepting community. The first time I marched in Mardi Gras, I was a champagne cork flying though the street, bursting with happiness and awe that so many people were affirming my identity. All I’d ever felt around being gay was fear and isolation and here I was exploding with joy and exclaiming “Happy Mardi Gras!” to thousands of new friends!

As I began to explore the scene, I discovered I wasn’t as sexually daring as I thought I would be. It took me longer to trust and build relationships, and I rarely jumped into bed with someone I barely knew. I wanted to be bold and free-spirited, but I couldn’t work out what was holding me back.

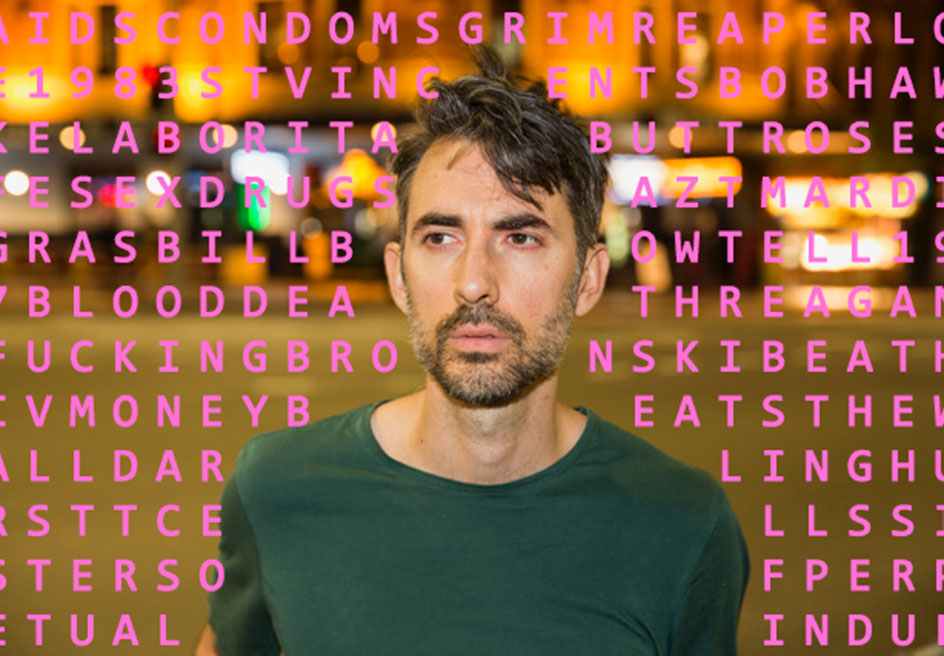

Credit: William Yang

A few years ago, I read a play called The Normal Heart by American playwright Larry Kramer. It chronicles the early years of the AIDS epidemic in New York through the eyes of writer Ned Weeks as he forms community action groups and fights dogmatically for money for research, outreach and awareness. He pleads with his community to stop having sex to save their lives, while still yearning for connection and intimacy. And there it was. In that character Larry Kramer had distilled was an essence of my experience growing up in the shadow of AIDS. I set about researching more about this period and I found a book called Learning to Trust: Australian Responses to AIDS by Paul Sendziuk. The book details the history of AIDS in Australia from the early ’80s, and the innovative governmental approach and involvement of community action groups in forming policy and prioritising education and prevention.

As a storyteller, what struck me most about this Australian story was the fortuitous circumstances that allowed for Australia to have the lowest HIV transmission rates in the developed world.

In 1983, the Hawke Labor government had just been elected, and Neal Blewett was appointed federal Health Minister. Blewett chose a young diplomat called Bill Bowtell to be his senior advisor. Bill also happened to be an out gay man who split his time between Canberra and Darlinghurst. In their first week on the job, they were briefed on their portfolio and along with the re-introduction of Medicare, there was something called GRID or Gay Related Immune Deficiency, that was buried in the back. Blewett started asking questions that none of the public health servants could answer. The Chief Commonwealth Medical Officer at the time said “Whatever else it is, Minister, you can be sure that’s it’s not a virus.” Blewett was undeterred and Bill Bowtell took him to Darlinghurst to see how ‘druggies, poofters and whores’ lived their nightly life. As more reports came out of the US of rare cancer-related deaths in previously healthy young gay men, he realised the potential danger and didn’t waste any time.

In 1983, Bowtell and Blewett travelled to San Francisco and were given a tour of AIDS hospitals and watched in horror as patients had their food slid under their doors, and medical staff were kitted out like astronauts. Baptist ministers and televangelists were buddied up with Reagan, preaching the rhetoric that AIDS was God’s punishment. In their world, AIDS was the result of depravity, and not a health crisis that required pragmatism.

At the same time in Sydney, there was already a strong history of AIDS activism in groups like CAMP, the Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby, gay counselling services and Radical Women. In 1983, representatives from over twenty groups formed the AIDS Action Committee. Their aim was to monitor information about AIDS, and to provide non-alarmist information to the gay community and the wider media. They also set about establishing support for those who would become HIV positive. This was a group of fiercely intelligent and committed men and women who knew that this disease had the potential to set back all the aims they had been fighting for.

Bill Bowtell had previous links with these groups and could see that their education and outreach was the only way to prevent the spread of AIDS. All the theories relating to activities which spread the virus were illegal: homosexual sex, drug-use and prostitution. Gay men, drug-users and sex workers were transient, private people on the fringes of society. They were people that the status quo could use as a scapegoat because they didn’t fit into any template of normality. Bowtell realised that the only way to speak to these communities was from the inside.

At Bowtell’s insistence, Neal Blewett orchestrated a cost-sharing arrangement with the states which stipulated that at least half the money going toward the AIDS cause go to community groups to undertake prevention and education campaigns, much to the chagrin of doctors. This had never been done anywhere in the world.

Erotic posters and pamphlets extolled sexy safe sex, information hotlines offered options for alternate sexual practices: flirting, frontage, kissing and mutual masturbation. It was imperative that these communities had to talk about sex, and who knew better than the communities themselves.

These measures were incredibly progressive, especially in the face of religious groups calling for the ban of Mardi Gras, conservative politicians declaring high-risk individuals be quarantined, and a salacious media culture that printed opinions from people claiming gay men were deliberately infecting the blood supply. But the government and the gay community persisted and as they began to see friends, family and colleagues die tragically, the fight became very real and very personal.

Blewett and Bowtell had to find a way to quell the hysteria from the media and the general public, so they appointed Ita Buttrose as the director of the newly formed National Advisory Committee on AIDS. The committee was made of representatives from medical institutions, AIDS councils, sex workers groups and drug councils. In this way, everyone could see all sides of the disease and create policy from an informed and balanced position. Ita (being Ita) was also the perfect spokeswoman because people trusted her and she didn’t point the finger. She led the way and introduced the plight of AIDS to the mainstream.

In 1987 the Grim Reaper ad premiered on televisions across Australia. While there was a lot of controversy surrounding the campaign, ultimately it was a genius move and shocked everyone out of apathy. It was perfectly timed for the beginning of the budget cycle when the Minister met to discuss the government’s spending priorities. Given the public fear that was caused around the campaign, they were able to agree that money needed to be spent on AIDS before thousands of lives were lost. Up until that point, AIDS funding was borrowed from various streams, but after the campaign AIDS was given permanent funding, and AIDS councils and institutions were firmly in place to continue the work of education and prevention. It also persuaded State governments to implement controversial AIDS prevention initiatives such as syringe exchange programs and sex education in secondary schools.

This is the history of AIDS in Australia that I wanted to tell. In 2019, we live in a world that is so divisive, but AIDS was an issue where disparate groups had to come together despite their differences and make change. And change they did. And that saved lives. More than 25,000 of them. And the Labor and Liberal governments worked together helped to make this happen.

AIDS showed us that you can effect change, but you can only do that from a position of non-judgement. Everyone had to look at the facts and accept that they couldn’t act as a moral arbitrator. No one is innocent, everyone is flawed and no one has the right to stand in judgment. When we live our lives from this place, we tap into our humanity and discover it is infinite in its scope.

I can’t imagine what it must have been like to have your friends die around you before you had even turned 30. People had so many funerals to go to that they had to decide which one of their friends they would say goodbye to. What I realised as I delved deeper into the story of AIDS in Australia was that these men and women didn’t give up and live in fear, but overcame everything to care and love one another. I wanted to honour the people who lived and died in my community and who fought so bravely. I often think of all the wonderful creative men I never got to meet. They could have been my mentors, my friends, my lovers. I will never know the power of their human spirit, but their stories have given me strength to live boldly, and Never Let Me Go is my love letter to them all.