21.10.13

“Trauma, not war, is the subject of The Floating World.”

|

|

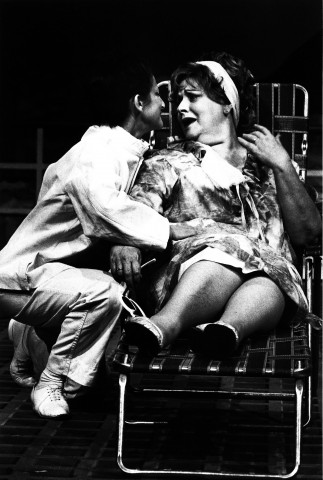

‘Waiter’ and Irene Harding in an early production of The Floating World. |

In his third and final blog, playwright John Romeril talks about the origins of The Floating World, and responds to the question, “Why did you choose to write about war?”

I am something of a ‘then’ playwright.

In place of scribing the ‘now’ (which I find intensely problematic), I spend a lot of time constructing ‘sort of’ histories and assembling portraits of the past. While at times I suspect I do the far less difficult thing, the best of my work examines not simply the past, but how the past impacts on the present. It uses the ‘then’ to put our ‘now’ into a politically useful perspective and to provide, in a small way, an antidote to our society’s cultural amnesia.

|

|

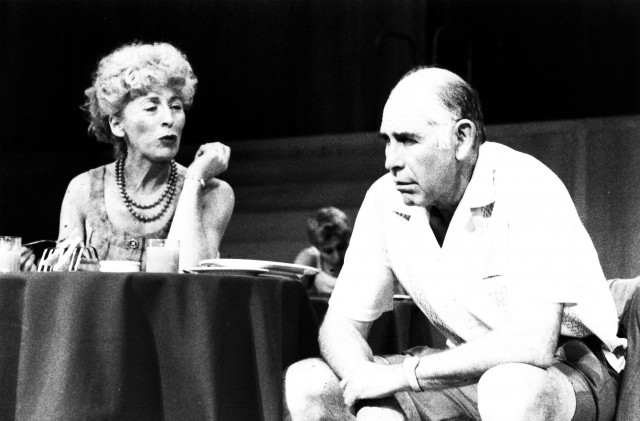

Irene and Les Harding in an early production of The Floating World. |

The Floating World began as an idiot play. While working as a librarian at Monash University, I’d taken to reading about the Noh and Kabuki theatres, and was by then well versed in haiku. The Japanese struck me as a very civilized bunch. I toyed with the idea of depicting the war in New Guinea as a cultural clash: the haiku versus the bush ballad – them descending on Lae with the highly stylised and codified body language of the Noh – us dying like footballers. Like I say, an idiot play. (I make no claim to being a deep thinker even now but in 1970 I was a moron. The fact is a lot of the world’s literature is produced by morons so I’ve never let it worry me.)

But a germ or two stuck. Vietnam was still raging. Australia was fighting its third war in Asia, against Asians. And New Guinea? My father had fought in New Guinea. In the end, I suppose my father was a key to the piece. A strange, moody, deeply insecure man, our last words, two years earlier, had been: ‘What’ll you do when they come here?’ ‘What?’, I replied, ‘they’ll be crawling through the hydrangea, will they?’ The subject was the Viet Cong.

Trauma, not war, is the subject of The Floating World: trauma occasioned by war. It was my contention then – and is still – that to have been alive in the twentieth century (and the twenty first, for that matter) is to be traumatised. The twentieth century was one of wars, revolutions, holocaust, genocide, socio-economic upheaval and mass dislocation. A century of disasters. Whether we write it or not – and if we can perhaps we are among the lucky ones – there is scarcely a citizen on the globe today who has not borne witness at some time, in some way to this inferno and as like as not been deeply scarred by that experience. It is a century you can’t get out of the road of. Flee to the forest but the acid rain will find you. There is no out. Just pain.

|

|

The ‘Entertainment Officer’ in an early production of The Floating World. |

Les Harding is not my father. He is my Everyman. He saw his tiny bit of hell, tried to keep the show on the road, but couldn’t. He is a product of his times: the depression that broke so many of his generation, the war where he’d missed death by a whisker, the 50s with all the rubbish that animal Menzies handed out, the grind of keeping a family on the road in a job that was none too secure. One more insane-makingly traumatic twentieth century Western individual. I suppose, when you write, having an Everyman eases the pain of having a father such as mine in a time like ours. My old man died another statistic in one more epidemic: that of stress related heart attacks amongst the middle-aged. May the earth rest his bones dead – it didn’t rest them living.

John Romeril, September 2013

Images provided by Currency Press