22.04.13

Our Affiliate writer Julian Larnach explains the myths behind The Bull, The Moon and the Coronet of Stars.

In my first year of an arts degree at university, I got to know the god of wine. Informally at first, through orientation mixers. It’s not to say all I did was drink; I was steadfastly pursuing the classical education I had read so much about. It was in my favourite class, Greek and Roman Myth, that I was formally introduced to Dionysus.

Although I had studied his PG-rated Roman doppelganger in high school, Dionysus exploded off the tertiary pages and overheads. He was the deity of grapes and wine, but also ecstasy and madness. He represented epicurean delights and orgiastic sex: equal parts Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and Keith Richards. He sat within Ancient Greece, which was a truly polytheistic society. The Greek world was united by the communal stories and accompanying festivities of their deities.

However, unlike other members of the Greek pantheon, the stories of Dionysus were different for every city – not just riffing on a common theme, they were seemingly unique occurrences. His stories followed a formula of arrival, destruction, conversion and departure rather than the usual story of “god sees X, morphs into Y, has sex with X then leaves”.

This narrative aberration led archaeologists and historians to believe the evolution of these stories was not one of a moral lesson corrupted through oral storytelling but rather historical documentation of a cult leader’s march of conversion around the Balkan Peninsula. This blew my mind.

The Greek myths I grew up with could be real. What, then, of the fanciful story of Ariadne? I pored over her tale, willing myself to know which parts were mythical tropes and which were fact that had been filtered down through millennia of Chinese whispers.

Ariadne was the princess of the island of Crete. Her father, King Minos, was once granted possession of a beautiful white bull by the sea-god Poseidon in exchange for its earthly sacrifice. Minos could not bring himself to do it, so instead kept the bull and roasted another in its place.

This angered Poseidon, so his sister—the goddess of love, Aphrodite—made Minos’ wife fall in love with the gorgeous bull. And, well children, when a woman and a bull love each other very much…flash forward, a half man-half bull Minotaur was born. The unusual creature had an unusual craving for human meat and so he was put away in a complicated maze-cum-cage known as the Labyrinth.

Years later, the Athenians killed Minos’ son after he achieved sporting glory on their soil. The Cretan king demanded penance for their action and so each year (or every seven, or every nine according to different sources), seven young Athenian men would be sent to the island as prey and eventual dinner for the Minotaur.

One year, the Athenian prince Theseus thought that the toll for his city’s sins had been paid and he decided to put an end to the beast of the maze. When he arrived, Ariadne fell in love with the young man and promised herself that she would not let him die. She secretly provided him with a sword to slay the Minotaur and a bundle of string to help him find his way out of the Labyrinth.

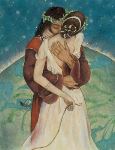

The sword worked, the beast died. The string worked, the prince escaped with the princess. But once back on his ship, the young prince had a change of heart and thought he could do better than the princess of an island whose fiercest asset he’d already defeated. He proposed a day trip to a nearby island where they drank and ate and frolicked and eventually slept. Thesesus awoke early and sailed back to Athens alone, leaving Ariadne alone on the beach of Naxos. It was here the god of wine—who could very well be a man—discovered her…