09.10.18

I’m a champion of killing the term ‘AV’.

It’s an archaic term that isn’t accurate, because it’s essentially ‘audiovisual’, and I don’t do audio, it’s all video—projection, or otherwise delivered. For this show, we have a projector and some screen content going to a television on the stage. ‘AV’ is a term that came out of the 60s and the 70s. I like to use a term called ‘integrated media design’, so that the visual media is there to support the text and to advance the story in a live context. I do a lot of different aspects of visual design, and video and filmmaking, from editing feature films and documentary, through to my own visual arts practice with installation, and I have a long history of working in visual design for theatre, so I ask that my contracts be changed and my billing changed away from that term of ‘AV’ to ‘Visual Designer’ or ‘Video Designer’. I’ve done a number of productions with wonderful sound designers, a couple of which we’ve had a joke going where they’ll be ‘Mrs A’ and I’m ‘Mr V’, because they do the ‘A’ and I do the ‘V’.

So I have very strong and detailed ideas built up over thirty years of doing this kind of work in the theatre, about how the video media should work within the frame of storytelling, which is what we’re trying to do with The Feather in the Web. This story has a whole lot of surreal moments, where Ben [Winspear, director] has directed blocking around these breaks in reality into these magical, surreal worlds. For me, the key discovery was to find ways for the video to help reinforce that, and to give the audience that extra element of dissociation and change in focus at various times. It’s a really wacky comedy that allows for a lot of extreme moments.

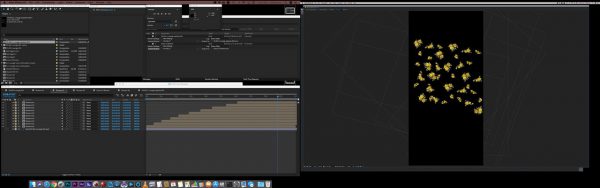

An example of Mic’s work for ‘Feather’ in Adobe After Effects

I worked in the theatre all of my adult life.

I started in a very broad arts degree, where I studied photography, editing on tape and on film, and a whole lot of life drawing, dance and drama, and I ended up doing a double major in dance and drama, and working as an actor and an acrobat for many years. Very early on, I was building sets and props to support myself—I’ve always been on both sides of the curtain, you might say—and I’ve also had a lifelong interest in video and editing. Increasingly, I started creating short films, and at the time when the digital revolution hit, I was well placed to transfer from tape-based editing to computer graphics and non-linear, computer-based editing of video. I then focused very heavily on film and video production, commercial and documentary video production, and I did all of the video production for Fashion Week for the first ten years it was running, and endless amounts of TV commercials and corporate work, as well as editing features and documentaries and drama for television.

All that time, I continued to have experiences working in the theatre, particularly around the mid-90s onwards—what I call an ‘invasion’ of technology in the theatre, because of the rise of digital technologies, digital video projectors, digital delivery for video… it really started to become a language that directors and writers wanted to use in the live experience. And because of my involvement in both disciplines, I was perfectly placed to start to work on bigger and bigger designs, and that really reached a peak around the first decade of the 2000s. For Opera Australia, I had the first ever Visual Design contract for the MEAA, which was back in 2004, I think. You’re kind of breaking boundaries, and at that time the Opera House had no Video Department, it was just a little bastard room off the side of the Sound Department, which is why I get fussy about the ‘AV’ thing… And in 2009, I did four main stage operas, and three main stage theatre productions, and that was a point where everyone was working with it. It’s been quite a natural process, and I think of it a bit as me coming back to the theatre, which I really love. I love being back in the theatre.

Josef Svoboda—Light and Shadow

It’s important to go back in historical terms to see that video design has been developing for a very long time, Svoboda and Cocteau in the 20s and the 30s, all the way through to what used to be the term back in the 60s, with Oldenburg and Warhol: the ‘multimedia experience’. You would bring different mediums, different disciplines, to play in live art. Now we have such strong commercial and cultural drivers, whether it’s the total immersion in screen technology that’s now the basis of our life, what with phones and televisions and tablets everywhere. But also, the state of the public now is such that the audience is very cinematically literate, they understand screen languages very well. It’s interesting for me now, that more and more, I see that young writers… in the past it was an addition that could be used on top of the text, but more and more, young writers like Nakkiah Lui are writing media design deep into the structure of the play, of the live experience, because it’s a given. Screen media is a huge part of life, it’s everywhere, so people see it as part of their creative process.

There have been amazing shows that I’ve seen that profoundly affected me.

Back in the early 90s, La La La Human Steps, a Canadian company that used a whole lot of large-scale film projection in dance and physical theatre works, was very influential for me, and LePage’s works. Some of the most satisfying shows that I have done often involve meeting and working with communities and groups. There was one show called Ngurrumilmarrmiriyu (wrong skin), directed by Nigel Jamieson, a story about skin and moiety in the Yolngu community up in Arnhem Land, placed in the frame of Romeo and Juliet, an impossible love story. I got to live and work with that community, and tour for a couple of years, so I was privileged to be a part of that community for that time. There was one particular point where we needed funeral footage, and the mother of one of the Djuki Mala… the Chooky Boys, her husband had recently died, and she gave us permission to use the funeral footage, and that kind of powerful, emotional experience, and then integrating that into a show, where you feel the absolute power and purity of it, and the way that that can absolutely supercharge the audience experience of something, that’s where things start to become incredibly affective.

Ngurrumilmarrmiriyu (wrong skin), directed by Nigel Jamieson

Working on Feather has been interesting for me because I’ve been busy on a number of projects, so I’ve come in at a reasonably late stage. But as usual, I work collaboratively with the designer and the director, and sometimes the writer, and in this case, I initially had broad discussions with Ben, and then a number of meetings with Sophie [Fletcher, designer], and then we went through the very specific concept she had around the printed screens and the relationship between the printed material and the video material, so that was quite an exciting and fun thing to think about playing with. Then I prepared a whole lot of stuff based around those discussions, and we’ve been in the theatre working very much with Ben, and there’s a lovely collaboration there of expanding and fine-tuning, and creating other cues and ideas as they occur. One of the great things about theatre is that it’s a collaborative form, and for Feather, the collaboration has been with the director and the designer, but also Trent [Suidgeest, lighting designer], who is a fantastic collaborator, and the collaboration between video projection and lighting design is really important. Trent’s great because we have worked together before, and we both have a very positive attitude in trying to find the best way to blend those two elements together. Essentially, in the end, it’s all light, it’s all projection or fixtures, and we have moving lights in this, with gobos, so we can do a lot of blending things together. So working with other designers and working with the director, it’s a great process, and this one’s been a good one.

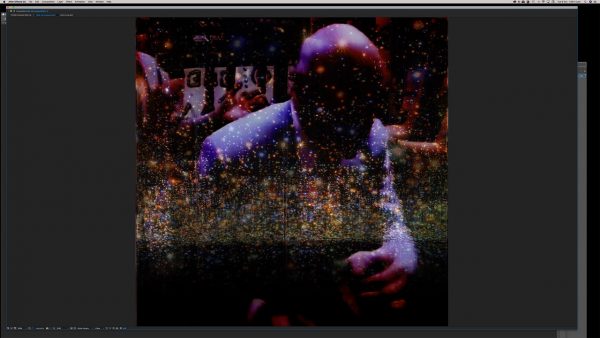

Video design for The Feather in the Web, by Mic Gruchy