01.02.19

Designer Genevieve Blanchett muses on the different places her wonderfully varied career has taken her, as well as her approach to designing Dead Cat Bounce.

I went to NIDA and did the Design course, pretty much straight out of high school.

I was very young when I got accepted—I was nineteen. That’s where my design career started for me, it was a great education, I learnt how to work. And from there I was very lucky that my first show was a mainstage show at State Theatre Company of South Australia. I did a few shows down there, and then it sort of blossomed from there, so it was pretty straightforward.

I’ve had a very diverse career, and that speaks to the fact that I really don’t like being bored.

I realised this when I was at high school—I’m sort of half-artist, half-scientist—so that’s always been a tension in me. I think in 1999, or maybe 2000, I received two large travelling grants from the Australia Council and from NIDA which was an amazing gift and opportunity. It was marvellous professional development for me as an artist, but it also exposed me to really serious issues in global politics that, because I’d had my head in my little theatre bucket for a long time, it was a real wake up call to me. I’m also a woman of extremes, so I felt the need to change up what I was doing and investigate what I could do about those issues in a more serious way, and that led me to working in Africa for a long time, and through that I came back to Australia for a while and trained as an architect, did some undergrad studies at ANU in economics, politics, history, environmental science, all of those types of subjects, because I wanted to understand what I didn’t understand, and I wanted to see if there was a way that I could use my design skills in a more practical way. That led me to architecture, then urban design, and working with communities. I went back to South Africa and worked for a long time with a township community on the outskirts of Johannesburg, and what I discovered, through all of my studies of built environments, was that somehow we’d always end up coming back to arts-based solutions when working directly with communities. That really stimulated again my hunger to be involved in the arts.

What I’m trying to do now is to run those streams parallel to each other, and find the opportunities for cross-pollination between the two worlds.

At the moment I’m working on this show with Griffin, which is great, and which satisfies that need for personal creation, and which communicates a really powerful story. I’m also working as an urban design activist with the Parragirls, out at the Parramatta Female Factory, and I’ve been working out there for a number of years as an urban design advocate at the state government level, but also on the ground, helping with the cultural development of that organisation, planning ways that the site can be activated temporarily using the arts, but also looking at its long-term future and driving that. That’s the kind of territory I’m working in now, and I’m really enjoying that.

I love having my head stretched in multiple directions. I find that thinking about really different things helps bring a really different perspective to the work that I do.

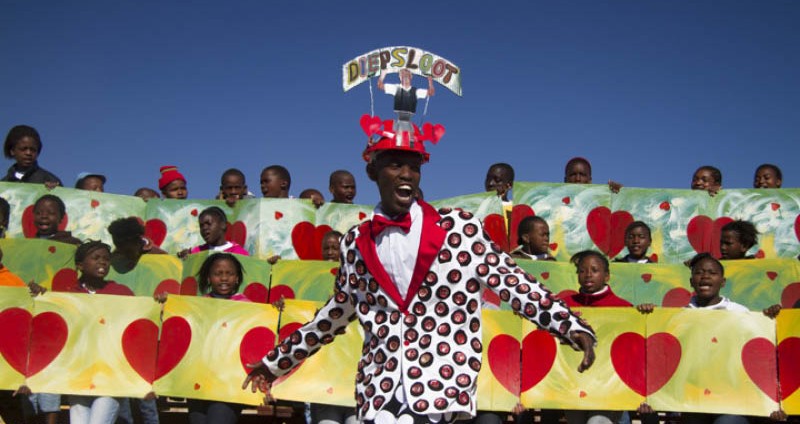

In Johannesburg, I was doing anything and everything. I made contact with the community through a studio that I attended, called the Global Studio at the University of Sydney, which was a partnership with Columbia in New York, and every year they would go to disadvantaged communities. My project ended up being a street performance that ended up communicating a number of the more standard architectural interventions being done by the other Studio group, and through that, we established a grassroots network, because we realised that that was the most powerful first step we could do. From there it was organisational development, business planning, all the while trying to find opportunities for income generation and employment for the artists… so yeah. Anything and everything. I mentored a lot of artists, and I’ve always done that—I’ve helped a lot of young designers get into NIDA, and helped them with their careers—but I was doing that on steroids in Johannesburg. We partnered with existing NGOs to create ongoing relationships, so I would broker those relationships; I worked as an urban designer with the Johannesburg Development Agency on a large urban upgrade, where I then slipped in the arts angle to provide opportunities for these artists, and through that we created this very large public art installation that had a performative aspect to it—that was a two year-long project. Yes. Anything and everything. With the skillset I have, I can move very quickly and in multiple directions at the same time. I’m not limited by what I can do. Never bored!

With my design for Dead Cat Bounce, we started as everyone always starts—with the play, and what the play is trying to say, and who these characters are, and what world they inhabit.

It became very apparent very quickly that the setting was not what was important—what was important was the dynamics between the characters—and in a way, any kind of naturalism would detract from the process that the characters were going through. We also—and this is just a natural impulse of mine—tried to transcend the naturalism that’s in the play, so that we wouldn’t create a realistic setting of everything, and detract from the play, just becoming “stuff” on stage. What we were trying to do was to unpack the emotional landscape, which is something I try to do with text-based plays, and that became the impetus for the design. It really leaves the characters nowhere to hide. It leaves only the barest minimal reference point to anchor them, to help Mitchell [Butel] with the action that needs to be done for the play, and to help manage the transitions between the scenes as elegantly as possible as the play goes on. Hopefully, the idea of starting somewhere, progressing on a journey, and ending somewhere else, makes logical, resonant sense with the emotional journey of the characters. It wasn’t really a research play, it was more of a thinking play—“how are we going to do this?”. It’s pretty simple, pretty empty, and I was pretty adamant that I wanted a “non-set” for this one. That’s something that I think, since I’ve come back to theatre, I’m less and less about the “stuff”, and more and more about the experience.

The collaboration process with Mitchell has been just fantastic.

I think Mitchell is the hardest-working man in show business, and we’ve been friends for a very long time, so it’s been a pleasure. It’s always nice working with somebody that you get on with personally, but he’s a real thinker as well, and being an actor, he brings that perspective with him. What I’ve really enjoyed working with Mitchell— and this is the first time I’ve worked with him as a director—is how smart he is at seeing the global picture, how on top of everything he is. And just generous—he’s really open to experimentation, really open to ideas that might be a bit scary, he’s willing to be open and flexible with things to allow them to find their feet, he’s not trying to control the process, but he’s got a real vision. I’m thrilled. Really thrilled.

I hope the audience doesn’t really notice my design. But I hope they feel it.

I hope it can do its job of transformation. And I hope they get the message of the play, which… Mitchell and I argue about this a lot, I feel it’s a bit bleaker than he does. I think there is hope at the ending, but it’s a very coloured hope, and it’s a broken hope as well. It’s quite tender. So I would hope that they feel moved, and that they feel a little shaken, and a little bit scared, in a way. And also that they’re not alone. Life takes very weird turns for all of us, and that’s nothing to be ashamed of, and that’s nothing to be frightened of. If you can open yourself up to the difficulties, and learn to be honest with yourself, and learn to be honest with others, then there is hope. I think that, for me, is the message of the play, and if people can walk away with a little bit of something that resonates with them in their own life, that would be awesome.